Without serious planning, district heating and cooling (DHC) will remain stuck behind gas boilers and heat pumps. Too often, cities produce glossy documents that never leave the drawer, or “heat plans” written solely to secure subsidies, which are worthless in practice. Real heating and cooling plans must prove affordability, involve all stakeholders, and be backed by strong political will.

By Per Alex Sørensen, Planenergi

Published in Hot Cool, edition no. 7/2025 | ISSN 0904 9681 |

Some years ago, I asked some of the largest DHC operators in Italy to explain the barriers to district heating and cooling. The main barriers that came up were:

- DHC is on the market and must compete with other heating and cooling initiatives (gas boilers and heat pumps). Price is the primary driver.

- There can be powerful opposition to new projects by existing utilities if they are not the owner.

- Lack of planning.

Some planning attempts are outlined in SEAPs¹ , but experience shows a significant difference between what is written on paper and what is implemented in the field. Planning documents are relatively poor instruments in convincing customers to use DHC. Often, urban planning is made without previous analysis. This represents a significant barrier to DHC, which requires community involvement to develop and implement network solutions. This is a political duty.

The conclusion was that heating and cooling planning is the key to the implementation of DHC systems. For EU countries, the Energy Efficiency Directive (EED 2023) requires Local Heating and Cooling Planning for cities over 45,000 inhabitants, but that will not necessarily pave the way for DHC implementation.

What is needed from heating and cooling plans?

To meet the barriers, there are four main requirements for heating and cooling plans if they are to pave the way for DHC implementation:

- A plan must include detailed calculations explaining DHC affordability compared to competing solutions.

- The plan must be produced in a transparent process explaining the advantages and disadvantages of DHC

- All main stakeholders must be deeply involved during the process – including utilities, citizens groups, politicians, and many others.

- A strong political acceptance and backup are required.

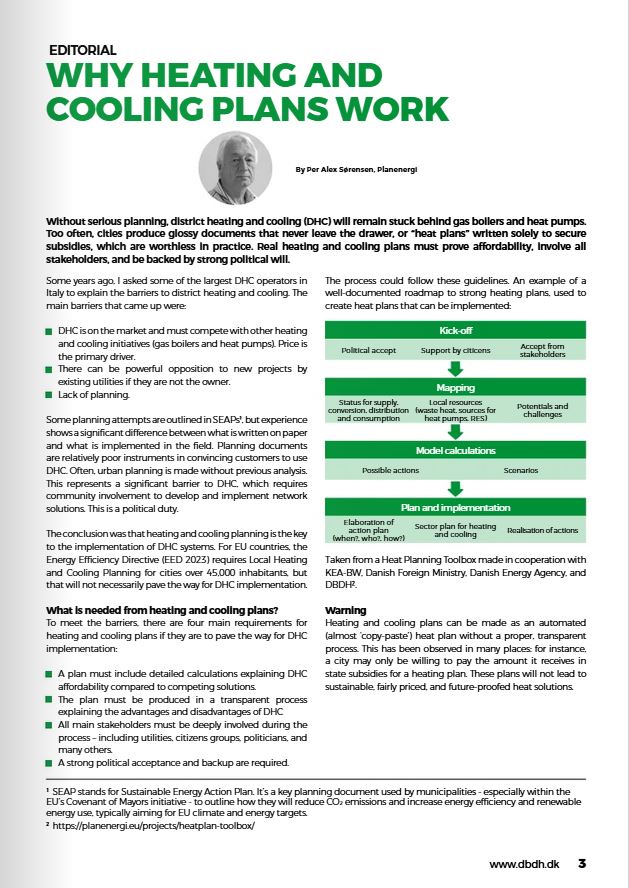

The process could follow these guidelines. An example of a well-documented roadmap to strong heating plans, used to create heat plans that can be implemented:

Figure: Taken from a Heat Planning Toolbox made in cooperation with KEA-BW, Danish Foreign Ministry, Danish Energy Agency, and DBDH².

Warning

Heating and cooling plans can be made as an automated (almost ‘copy-paste’) heat plan without a proper, transparent process. This has been observed in many places; for instance, a city may only be willing to pay the amount it receives in state subsidies for a heating plan. These plans will not lead to sustainable, fairly priced, and future-proofed heat solutions.

¹ SEAP stands for Sustainable Energy Action Plan. It’s a key planning document used by municipalities – especially within the EU’s Covenant of Mayors initiative – to outline how they will reduce CO₂ emissions and increase energy efficiency and renewable energy use, typically aiming for EU climate and energy targets.

“Why Heating and Cooling Plans Work” was published in Hot Cool, edition no. 7/2025. You can download the article here:

Did you find this article useful?

Subscribe to the HOT|COOL newsletters for free and get insightful articles on a variety of topics delivered to your inbox twice a month!